Will journalistic and other freedoms boom for this Baku youth the way everything else around him seems to be?

A couple of months after my visit, “Journalism 2.0” author Mark Briggs confirmed from Baku that “There certainly is a lot of interest in journalism for a place that has such struggles with it.”

From my latest offering in Florida Weekly’s Palm Beach Gardens edition, here. Or just keep reading:

And now, to be thankful for something completely different:

Unlike other places in the world we live in a country where, in the words of Stephen Biko of South Africa, “I write what I like.”

We get to cuss out our government officials, even question whether their birth certificates were stamped USA or Kenya, without putting our lives at risk like the anti-apartheid martyr.

In contrast, I met human rights attorney and distinguished former Azerbaijan Parliament member Matlab Mutallimli while in that country in March representing my colleagues of the international Organization of News Ombudsmen.

News ombudsmen field concerns at their news organizations and generally respond publicly.

In Baku, the Caspian sea capital of the oil-rich former Soviet republic that now is the Free Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan, the news the other day: “Azerbaijan must immediately release Eynulla Fatullayev.”

It was for his articles critical of the government that Mr. Fatullayev was arrested in 2007 and eventually sentenced to a cumulative eight years in jail on charges ranging from “Incitement of hatred” to tax evasion. So say his defenders, who include the Committee to Protect Journalists, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International and Reporters Without Borders.

For years Mr. Fatullayev suffered beatings, threats and the persecution of his family because of his outspoken journalism.

In April the European Court of Human Rights, whose rulings Azerbaijan is obligated to observe, found that Mr. Fatullayev’s rights of free expression had been violated and that he had been unfairly tried. The ECHR ordered his release with 27,822 Euros ($37,854) in compensation.

In July, however, Mr. Fatullayev was sentenced to an additional 2½ years on charges of possession of narcotics, which he says are routinely planted by Baku prison guards to silence critics.

On Nov. 11 the Azerbaijani Supreme Court agreed to implement the ECHR decision — while not addressing the drug charges. And in what the Committee to Protect Journalists called a ruling “blatantly tailored to defy the European Court’s order,” a Baku Appeals Court has said he will remain imprisoned while he appeals those charges.

Other Azeri journalists have been even less fortunate.

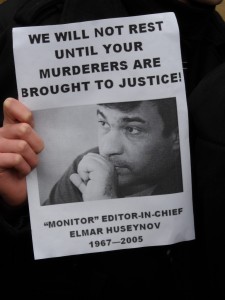

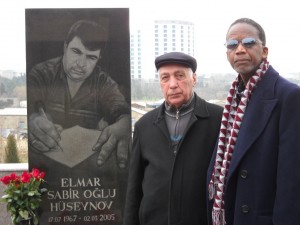

Enter my host, Matlab Mutallimli. While I broke from a whirlwind schedule of meetings and interviews with journalists and news organizations, he motioned me to follow him through a crowd to the front of a memorial service at the grave of Elmar Huseynov.

It was the anniversary of the brutal 2005 shooting murder of Mr. Huseynov.

The award-winning journalist had suffered threats and incarceration for his criticism of Azerbaijani authorities. He was fined and forced to close his popular Monitor after being convicted in 1998 of “insulting the nation.”

The view of many gathered was that the Azeri government was responsible for the assassination of Mr. Huseynov, who our U.S. ambassador at his first memorial service had described as a national hero.

I confess to having little clue about the challenges of establishing a free, democratic, post-Soviet era government.

As a journalist, I also don’t take allegations as givens, one reason I would have liked the organizers of my visit to have arranged for me to speak to “the other side,” so to speak.

Yet one of our government officials there has told me that as for higher levels, they are not open to such meetings. They’ve heard it many times before. Ahh, progress on media? Not really.

A couple of months after my visit, “Journalism 2.0” author Mark Briggs confirmed from Baku that “There certainly is a lot of interest in journalism for a place that has such struggles with it.” Among the hurdles he cited:

“News outlets must receive a special license from the government, which means there is little investigative reporting. (The government doesn’t tolerate criticism.) Independent news sources, mostly online, apparently operate with a single-minded focus on complaining about the government, so the idea of journalistic objectivity and fairness are a ‘are work in progress,’ to put it mildly.’ Still, many journalists I spoke to are hopeful that the Internet will change the game and bring a diversity of voices and reporting to a nation that sorely needs it.”

And the fact that there is no news on regulating the Internet is one place where there is some hope.

Our own news media are not guiltless, of course.

I’ve mentioned before my ombudsman colleagues chastising us U.S. media types for cheerleading our nation and the world into the Iraq disaster. Just this year, we have endured another round of idiotic media fascination over whether President Barack Obama was born in the USA or is a closet Muslim. We’ve had journalists give carte blanc to “angry” folks who threaten to tote weapons to public rallies, rather than call it out as the thinly veiled thuggery that it is.

And sure, our radio and TV blowhards get to say pretty much what they want. But our government doesn’t make us listen. We all get to tune them out. Because — in popular culture jargon — that’s how we roll.

It’s just more of our freedom that we should not take for granted.

So thanks, Dear Readers — especially those of you who fought and marched and even died — for my freedom to write what I hope you and I like.

Thanksgiving Day addenda:

Voice of America: Azerbaijanis Blog for Freedom

MSNBC: Azerbaijan frees second critical blogger

— C.B. Hanif

No Comments so far ↓

There are no comments yet...Kick things off by filling out the form below.